Scanning Around with Gene: Makin’ Pages With Bruce

When Bruce Springsteen played the halftime show for the 2009 Super Bowl, it sent me into a bit of a funk. Not because of his performance, which I actually slept through, but because it served as a reminder of how far my own career has come. Bruce and I go way back when it comes to setting type and making pages. In fact, listening to Springsteen and wrestling with graphic arts are the two most constants in my life.

Had it really been more than 35 years since I picked up my first pica pole and set to work building a page? And what do I have to show for it? In that same time Bruce Springsteen managed to accomplish much (like becoming a god), and all I learned was how to set 12 pt Helvetica on more machines than I care to remember.

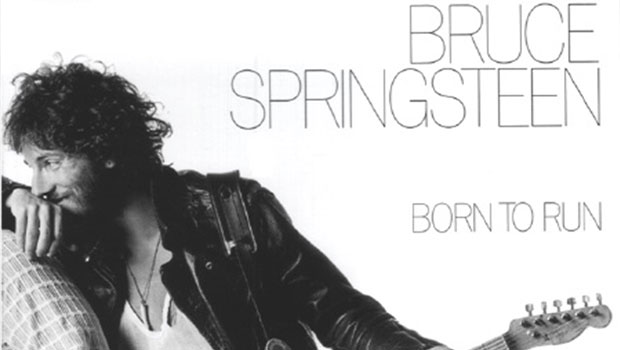

But then I do get to write this column, and while it’s not quite the same adrenalin boost as, say, belting out “Born to Run” in front of 100,000 screaming fans, it always cheers me up. So I thought this week I’d parallel my own career and some key developments in computerized typesetting with Bruce’s career.

1973 – Growin’ Up

Bruce is older than me, so we didn’t exactly start off as equals in our crafts. In 1973, when Greetings from Asbury Park came out, I was a high school student and more interested in the Doors than Springsteen, but I did get a few listens on Los Angeles FM radio. I was working on the high-school yearbook trying my best to rub down dry-transfer type without it falling apart and coming out crooked, and I learned to use a Scale-O-Graph cropping device on pictures.

While Bruce was being blinded by the light, Compugraphic (now Agfa) introduced a record-and-playback feature (using magnetic tape cassettes) on a direct-entry phototypesetter. For the first time, an affordable machine could do it all: — input, output and storage. It was inevitable from this point forward that setting type would become somewhat of a commodity.

1975 – Night

I remember the first time I heard the song “Born to Run” on the radio while I was going to college. It was late at night and I was driving in my yellow Opel (which use to be sold in America by Buick) to the student newspaper office. There the other students who also couldn’t get a date would pull all-nighters, trying to get out an issue. The song was infectious from the first (as was pulling the all-nighter), and I remember for many weeks listening intently to the radio, hoping “Born to Run” would come on again.

I got to listen to the radio a lot that year because I practically lived at the newspaper office. Not only was I giddy with the self-importance of being a journalist, but we had just installed our own little production department (including a CompuWriter, pictured above), and I immediately assumed the role of production manager, tour guide, and trainer — anything that put me in charge of the many switches and buttons that needed to be set properly.

The important message from this period is that, in those early days of computer-driven machines, the main attraction to the field of setting type and constructing pages was a mechanical one. It wasn’t quite chrome wheeled and fuel-injected, but I did love strapping my hands across those filmstrips.

1978 – The Promised Land

Darkness on the Edge of Town is my favorite Bruce Springsteen album, and 1978 is about my favorite time in typesetting. This was the era of the Compugraphic Editwriter 7500 (shown above), one of the breakthrough machines in the long march from big, expensive, proprietary systems to “desk-top,” (if you’re willing to allow that the desk is part of the top).

Plus, the Editwriter was fun to operate, easy to run, and it didn’t jam up as much as other machines. They ran on CPM, an early predecessor to DOS, and if you could get a bootleg copy of an 8-inch disk from the Compugraphic repair guy, you could play Pong on it. I loved these machines, and still have a can of Compugraphic Blue touch-up paint that came with the machine when it was installed.

The Editwriter (and machines like it) fueled the birth of many weekly newspapers, small magazine publishers, and all sorts of alternate press. And though the Macintosh would have an even greater effect, this was the first time that nearly any passionate and modestly resourceful person could become a publisher. I spent many a night those days proving just that.

1980 – Independence Day

I was usually a few generations of technology behind, simply because I always worked at low-budget operations. So in 1980 I was still mired in film-font machinery — where light passed through some sort of film master and exposed to a photographic surface. While more consistent than metal type, when you factored in scratches, temperature changes, exposure times, etc., etc., the type coming out of these machines was hardly perfect. But out in the street everyone else was going digital.

It’s no surprise, then, that The River was one of the first major albums recorded digitally. This was a year of many digital breakthroughs — machines like the Alphatype Multiset III (pictured above) had up to 80MB of memory, a 16-bit processor, hard disk storage, and the sophisticated hyphenation those things made possible. Exposure was with a cathode-ray-tube, which made for type that was nearly perfect, every time. But more importantly, it meant you shouldn’t have to wait two or three days for your job to be done. The ties that bound us to chemicals and darkrooms were becoming a thing of the past.

1984 – Glory Days

I didn’t really embrace the album Born in the USA when it came out, which makes it the perfect parallel to the other things going on in 1984. Suddenly everyone was a Springsteen fan, he was all over MTV, and it seemed like amateurs were taking over my beloved icon.

So when the Macintosh was introduced that year, and Steve Jobs connected with John Warnock and Check Geschke of Adobe (pictured above) to make the Laserwriter, I wasn’t impressed. Mine was a craft, learned through hard work and frustration. Setting type was something you endured to produce the final results. The idea that it could be made easy was completely at odds with several industries, a considerable economic juggernaut, and all of us who had spent nights cutting corrections in one letter at a time.

But of course this is the year when everything changed. Many would be crushed, quite a few would simply give up, and others would jump in with enthusiasm and promise. Like it or not, both my musical and type preferences were opening up to a mainstream audience, though for several more years I refused to retreat or surrender, and stuck to my traditional typesetting ways. But of course, I was just dancing in the dark as we all now know.

1992 – Better Days

By 1992, when the album Lucky Town came out, like Bruce I decided to give up my old ways and depart on a solo career. He dropped the E Street Band and I decided to join the desktop revolution and embrace the very technology that was putting my typesetter friends out of business.

By then the Mac was beginning to be good enough for quality production, Adobe was making inroads, and Quark was blazing a path to success. I went to work as an editor at Publish magazine and began many years of fun and gratifying work covering the graphic arts industry. Rather than regret every new development, I started looking forward to it, and since we produced the magazine with the technology we wrote about, I felt like we were part of the progress being made by an industry desperately trying to meet high-end standards.

2002 – Into the Fire

The decade from 1992 to 2002 was an exciting and rewarding one for me, even if it wasn’t as prolific for Bruce. Yet by 2000 it was clear some things just couldn’t last. I was running the Seybold Seminars events at that time, and our September San Francisco show that year was the most successful ever. But on the last day my sales manager and I walked the show floor, looked at each other, and said “This is it, you know — the industry can’t sustain this sort of growth and by next year a lot of these companies will be gone.”

So even without the hit of September 11, 2001, two weeks before the next year’s show, it was clear all the fun was over and only struggle and heartache lay ahead. We pulled through that September, barely, but I knew both my career and the industry I loved had changed forever.

In 2002 when Bruce released the phenomenal album The Rising, we had just decided to move our East Coast event back to New York, partially as a show of support for that city. His album was brilliant and captured the sadness, heroism, and hope of the past year. Our show was less than brilliant, and it marked the end of an East Coast Seybold event.

So by September 2002 when we returned to San Francisco, I already knew that show would be my last, as I planned to quit as soon as the wrap-up was done. I was tired of laying off people, dealing with maniac executives, and trying to convince people there was still anything truly happening in the creation of printed pages. The Web was the thing by then, and even though we had tried very hard to align the Seybold brand with those kinds of pages, it was a different culture that didn’t attend our kind of tradeshows.

I did, however, act on a whim and set up my garage letterpress shop (above), which played on both the potential and dread I felt at the time. If things were all different now, maybe a return to the past would give me hope and inspiration.

2003 – The Greatest Hit Years

After The Rising, Bruce didn’t do a whole lot, and neither did I. He came out with a series of greatest-hit compilations, and I thought maybe I could rest a little on my own laurels and trade in some of my experience for a less-hectic lifestyle. The only difference, of course, was that he had talent and all I had was a long resume.

But nonetheless, I was pretty full of myself and designed a pretentious logo (above) and set out to do whatever sort of work people would pay me for. I do have at lest one thing in common with Bruce during that time — we both took off from our main careers to raise kids, in his case a whole family, and in mine a wayward nephew. I don’t know how his turned out, but my experience was not a big success.

2005 – Devils and Dust

When Bruce’s album Devils and Dust came out, it was in sync with my life at the time. The title alone describes where I was: My print shop was covered in dust and I felt every day as if the devil was working against me. Like Bruce, I was working alone, had a gloomy outlook, and was tending to find the worst in everything.

Every so often Bruce manages to put the old E Street Band back together and go on the road, which I know is probably key to his survival. As much as you want a break from the hectic pace and weariness of life on the road, if you don’t get out there your world gets very, very small and petty. I’m at that point now. I once travelled around the world and flew so often I came to know gate agents by first names. Now I sometimes don’t get out of my sweats for days at a time.

2009 – Working on a Dream

Bruce has a new album out and here I am, still holed up in the darkness at the edge of my garage office, getting depressed and checking the Huffington Post way too often. So I’m taking his new release as a sign that it’s time to work on my own dream. Don’t ask me what it is just yet, but I’m going out today and buying the new album in the hope that as he has so often before, Bruce can inspire me to get off my ass and find out what I got.

This article was last modified on March 24, 2021

This article was first published on February 13, 2009

For me working in the manufacturing aspect at Compugraphic Corp In the 70s brings back memories. I liked assembling and testing the machines but Compugraphic at the time did not value there employees. In the Lowell Ma area they where the largest employer with over 6,000 employees. As I can remember there were 10,000 Editwriter produced thru 1977-1979. The Editwriter 7500 was ahead of its time .

During my apprentice years I started with the “California Job Case” and composing stick then came along the AstroComp TXT not too long after the MultiSet. The typesetting industry change so drastically and so fast. I was young and versatile at the time too experience it all and then some . . . and stilll in the business . . . Should have listened to my mother !

gofishron@hotmail.com

I learned to set type on it, and would love to have a high res photo of that terminal. Got one?

oshma@hotmail.com

Thanks for another entertaining and sincere article, Gene. You’re a great writer, and a advocate for us graphic artists who were true craftspeople and started using phototypesetters, finally joining the personal desktop era.

You can relish in the fact that you’ve seen the industry grow so immensely throughout the last few decades and we look forward to hearing what you have to say as the field continues, inevitably, to change. Thanks, as always, for telling the story of our craft!

Wow your column hits to close to home Gene so if nothing else just know you are not alone! I dont’ have your experience I came into graphic design (acutally working and getting paid for it that is) just as typesetting by hand was going out and Mac was coming in. By the sounds of your articles I’m probably about 12-15 years younger than you, in my early 40s now and fearful – I’m not sure I can keep up with technology as fast as it moves. BUT i read you columns frequently I don’t think you can be a good designer web or print without looking at the past and PLEASE keep that in mind when you are looking for what you have to offer next – your experience and knowledge is priceless!

Michelle

I used to use the EditWriter back in the late ‘seventies. Looking back on it, it was my introduction to working with computers and files. I never knew it ran on CP/M. What made it so easy to use was that it only did one thing–set type–and almost every command had its own key on the keyboard.

Just to let you know, your column is always a bright spot in my day.

Remember “Nebraska”?

Everyone has at least one rough patch.

It builds character.

I went through a slump a few years ago and pulled out with the help of an old friend (now sadly gone) and a hands-on, do-it-yourself, physically exhausting backyard project rebuilding a boat.

This little essay of yours shows me you’ve got plenty left in you.

I hope I don’t come off as patronizing–I’m just a fan.

“Bruce can inspire me to get off my ass and find out what I got.”

Actually, I’m reading it as “Gene can inspire me to get off my ass and find out what I got.”

Most excellent writing, Gene. Thanks for the inspiration.

Billie Brown

Drama Dog Design

Gene,

You’ve captured a lot of my own experience with your parallel life. Your vehicle of plotting the rise and fall of the graphic-arts/typographic professions via The Boss’s albums and career is inspired. I’m not much of a Springsteen listener myself, but I feel your pain, amigo. There’s a genuine sadness in your story that I suspect includes a lot of grief for the (sorta) end of our industry, along with your personal tribulations of course.

I hope you pull yourself out of the doldrums soon… the world is still there waiting for fresh eyes to see it. Believe me… I’m only too aware of the challenge.

Best of luck!