Creative Fuel: Death of a Hero

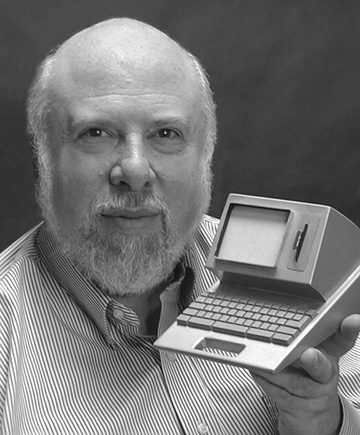

Jef Raskin, a gifted technology designer, artist, educator, musician, and pioneer of the original Macintosh, died on February 26, 2005, at the age of 61. Raskin was responsible for some of the things creative professionals like best about computers today, and he never stopped trying to improve on some of the things we hate the most about computers. I never met him, but when I heard the news of his death, tears came to my eyes. Although many creative professionals may not know his name, the entire graphic arts industry owes Jef Raskin an inestimable debt of gratitude.

The Macintosh computer established Apple as a force in the nascent personal computer industry. It also paved the way for other companies, such as Adobe Systems and Quark, to create products that rapidly changed the graphic arts industry. Its (at the time unique) graphical user interface was a key element in its success with graphic arts professionals.

History In the Making

For those of you too young to remember, the Macintosh was not Apple’s first computer. Apple got its start in the late 1970s selling the Apple I, Steven Wozniak’s first mass-produced computer that zipped along at a (then) speedy 1MHz. When the Macintosh project got underway, the company was selling the Apple II, another 1MHz computer with 4KB of base RAM. It could display color graphics — a real rarity in those days — at a maximum resolution of six colors at 280×192 or four colors at 40×48. The system came with an optional floppy disk drive and a keyboard; the mouse was an innovation that came a little later.

In 1979 Jef Raskin, then employee number 31 at Apple, suggested to Mike Markkula, Chairman of Apple’s Board, that the company ought to design a new computer. Despite opposition from Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, Raskin got the nod and spent the next three years working on the Macintosh project. (That catchy name wasn’t a marketing department invention. Raskin named the computer after his favorite variety of apple.)

During his time at Apple, he put into practice many of his interface design principles and invented many elements first used by Apple computers and in the Windows operating systems. In 1982, citing creative differences with Jobs and others, Raskin left Apple to found his own company, Information Appliances Inc. For the last twenty-five years of his life, he focused on creating improvements in computer interface design.

Although computer historians can, and probably will, continue to debate who deserves the greater share of the glory for creating the Macintosh, Raskin was undoubtedly one of the Founding Fathers. He had a deep and rare respect for the design process and for designers, and he never stopped trying to improve computer interfaces. According to a press release issued by his son Aza, Jef Raskin worked until his last days on Archy, an open-source redesign of computer interfaces that exemplifies his most profound principles.

Memory, Envy, and Gratitude

It’s hard to encapsulate in a few sentences the cascade of memories and emotions that washed over me when I heard that Raskin had died. Immediately I recalled the first time I saw a Macintosh. In the days when PCs were expensive novelties, I was taking courses in mainframe COBOL programming at a nearby university in the evening. Having recently graduated from college with a liberal arts degree, I was trying to improve my earning capacity by learning computer programming languages. I wasn’t enjoying myself too much but was determined to learn what I could.

I remember hating how the mainframe was locked up inside a big glass cage and accessible only to its consecrated attendants — grouchy and uncommunicative computer science graduate students. We lowly continuing education students had to plow through huge, thick books of programming commandments stacked around the rim of the room to get a hint as to why our code wouldn’t run.

I was standing at one of those books in the computer lab one evening when the sound of a door opening drew my attention. Turning from the code bible, I saw, through the open doorway, a room filled with small computers. I knew they were computers and that they were Macintoshes because I’d heard people talking about them. I was filled with envy. I wanted a computer that was all mine, a computer I could touch.

Years later, after I had put in a few years selling personal computers, I got a job testing PC hardware and software. I was paid to be frustrated, and I got to write about my frustrations. Things haven’t changed much since then, I suppose, except I’ve gotten more relaxed about aggravations caused by computers. I guess I’ve learned to be grateful for the benefits of the technology and can live with the limitations — most days, that is.

I may be more laid-back about the realities of daily life with a computer, but I think it’s terrific that Raskin never stopped trying to improve the beasties, even to the point of reviewing his own earlier work for improvements. In an interview conducted by a University of California: Berkeley radio station in March 2004 to honor the occasion of the Macintosh’s twentieth birthday, Raskin talked about ergonomic studies that show most of the repetitive stress syndrome problems people experience with computers stem from the use of the mouse. He described how and why he would redesign the mouse if he had it to do all over again.

It was also in this interview that Raskin talked about some formative experiences that helped him in designing the Macintosh interface. As I read his remarks in the transcript, that indelible memory of my first glimpse of a Macintosh came back to me again, along with another tear or two of appreciation.

He said, “When I was a graduate student in computer science at Penn State, because of my strong interests in the arts, music, and visual arts, I was assigned the task of helping people in the computer center, for people who were in the fine arts or the liberal arts, and they were struggling to use the computer. Most of the other computer science grad students had the opinion that there were those people who got it and those people who just don’t get it. But once I observed them working, I realized it was not the people who were having the problem, it was the fact that the way our computer systems were designed was giving them all the problems…and I realized that we should be designing computer systems to make them easier to use and that was more important than what I was being taught in my computer science classes.”

I’m glad he was paying attention. Aza Raskin plans to continue the work his father began. To learn more about that work, including Archy, visit the Raskin Center online.

This article was last modified on January 26, 2023

This article was first published on March 10, 2005

Interesting and enlightening. Thanks.