Heavy Metal Madness: Macintosh, Mackintosh, or McIntosh?

The night was dark, and stormy. It was January 24th, 1984, and I was sitting at a table in Carmel, California, waiting patiently while two coked-up restaurateurs reviewed the latest changes to their menu. I was a typesetter at the time and I had grown accustomed to this drill in which the client used the final paste-up as an incentive to make fundamental business decisions that would, of course, mean completely re-doing the job. In this case the proprietors were wildly gesticulating and pleasing themselves no end by coming up with clever names for sandwiches, pasta dishes, and appetizers.

It happened to be Super Bowl Sunday, and though I had no idea who was even playing, sheer boredom and the offer of free beer eventually led me to watching the television that was on in the background. The setting was already pretty surreal when the now-famous Apple “1984” ad came on and set a tone that made the futility of my current situation seem even more pathetic than it was. Apple announced to the world that it had arrived, and was, as usual, ahead of the pack. This 60-second spot directed by Ridley Scott kicked off the era of extravagant Super Bowl advertising, and launched the Macintosh at the same time (see Figure 1). None of us in the graphic arts had a clue what that day really meant.

Figure 1: The Macintosh 1984 ad was actually conceived in 1982 for the Apple III release, and despite common belief, it did not run only one time during the Super Bowl. The ad ran first on December 15, 1983 at 1 A.M. on station KMVT in Twin Falls Idaho-a quiet pre-airing so ad agency Chiat/Day could qualify it for the 1983 advertising award competitions. The Apple board of the time hated the commercial and at one point Apple founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak discussed splitting the $800,000 advertising charge between them in order to assure that the commercial aired.

Of course the restaurant was soon out of business, one of the ambitious cokeheads later died of a brain aneurism, and I would ultimately lose my type business and embrace the Mac (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: From heavy metal to insanely great. The Linotype (an Intertype is pictured here) was invented in 1886 and lasted for nearly 100 years before being unseated by the upstart Macintosh, which was first released in 1984.

So here we are, 20 years later, wondering what might come next. Maybe this Super Bowl Sunday we’ll be blown away again, though I doubt it. In the mean time, I thought a look at all things Macintosh would be in order.

An Apple a Day

The Macintosh project began at Apple as one code-named Annie, and spearheaded not by Steve Jobs (he actually lobbied against the Mac project at one point) but by Jeff Raskin, a former computer professor and Apple employee number 31. Raskin is generally credited with quickly changing the codename from Annie to Macintosh, an obvious tie to the Apple brand. Macintosh was spelled differently than the apple variety, however, in an unsuccessful attempt to avoid trademark disputes. Apple itself, lore has it, was named by Steve Jobs for either his love of the Beatles (and their Apple Records label), his interest in health foods, or because of his fond experiences working in the apple orchards of Oregon during a brief stint at college there. Or for none of those reasons. Except for the short-lived Pippin operating system, Apple the company thankfully avoided any other product references to varieties of apple, the fruit.

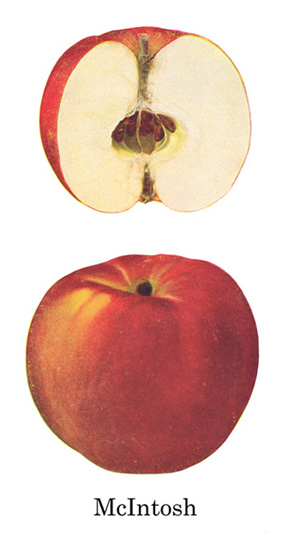

The origins of the real McIntosh apple are very clear, and there doesn’t seem to be any code names involved. This sweet but slightly tart red fruit was named in 1811 for John McIntosh, the American-born son of a Scottish immigrant. The original McIntosh apple tree was grown in Ontario,Canada, and grafted rapidly to become the dominant variety grown in the Northeast United States (see Figures 3 and 4). That first tree was damaged by fire in 1894 and bore its last fruit in 1908 — almost 100 years of faithful service.

Figure 3: The apple McIntosh is a very juicy variety grown from September through June in the northeastern United States and Canada. It has tender, white flesh and is excellent for salads and pies.

Figure 4: Even Santa prefers a Mac, as depicted by this picture from an Apple Growers Association public-relations campaign.

The Clan of Mackintosh

So the Apple Macintosh was named for the apple McIntosh, which was named for the Scotsman, McIntosh, who came from a long line of McIntoshes, dating back to the third Earl of Fife, who in 1429, actually spelled his name Mackintosh (from Mac-an-Toisch, which means “Son of the Thane or Chief”). But no matter how you spell it, Mackintosh, McIntosh, or Macintosh, the origins all trace back to the original Scottish clan (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: The Third Earl of Fife is thought to be the beginning of the Mac clan in Scotland. What type of computer he would prefer, we’ll never know, but he cuts a wide swath in his stylish kilt.

There are plenty of proud Mackintosh’s still around, and you can join various clubs, pipe and drum bands, or haggis-cooking groups if you are so named or inclined. There is a Yahoo Clan Mackintosh of North America Group with 20 members, and a host of Websites devoted to the clan and its tartan patterns (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: The Mackintosh clan’s dress tartan. I don’t get the whole tartan thing, but there appear to be many varieties within each clan, reserved for various occasions or circumstances.

The Mackintosh You Wear

The name Mackintosh, or Macintosh, or McIntosh is not just on a Scottish coat of arms, it’s associated with another type of coat entirely. An industrious Scotsman, Charles Macintosh (note spelling) was born in 1766 in Glasgow, and would go on to become an eponym for raincoats, particularly those that are belted around the waist. After studying chemistry, Macintosh went to work in his father’s fabric plant and began experimenting with rubber as a waterproof coating. By mixing the natural rubber with coal-tar naptha, in 1823 Macintosh was able to patent the first waterproof material. Coats made from this material became known as Mackintoshes, or “Macs,” but it’s not known why the spelling changed from the man to the coat (see Figure 8).

Figure 7: In 1838 Hodgman and Company manufactured stylish Mackintosh coats from their factory in Framingham MA. The company still exists {www.hodgman.com}, though they no longer support the Mac.

Figure 8: The Brits really know how to have a good time, even in the rain. That’s why they’ve grown so fond of their Macs.

The first Macs were problematic, becoming very stiff in winter and sticky in summer. It took Charles Goodyear’s 1839 discovery of vulcanization to firm up the Mac’s role as the preferred type of rainwear (see Figures 8 and 9). Charles Macintosh was not only into rubber, he and his partner Charles Tennant perfected a method of bleaching that was widely used in the paper and fabric industries . And if that wasn’t enough, Macintosh also helped refine the hot-blast process of smelting iron.

Figure 8: And the banker never wears a mac, in the pouring rain. Very strange. Two shining examples of classic Mackintosh rainwear from the Dunlop Tire Corporation. Thanks to Charles Goodyear, rubber outerwear became a practical way to keep out the elements.

Figure 10: Not everyone who collects Macs is in it for protection from the elements. If your obsession with your Mackintosh borders on the unhealthy, maybe this magazine from the fetish club the Mackintosh Society is for you.

Mackintosh, the Architect

In the architecture, furniture and design worlds, Charles Rennie Mackintosh is a standout, leaving behind a distinct style that is widely admired and copied. As a 28-year old art student in Glasgow, Mackintosh won a competition to design a new School of Art there. He went on to design not only distinctive buildings, but highly original furniture, stained-glass windows and other ornaments as well (see Figures 11, 12, and 13). Combining a love of Japanese style and art nouveau, Mackintosh became the Scottish equivalent of Frank Lloyd Wright. He incorporated his design style throughout all the elements of a building and its furnishings.

Figure 11: Charles Rennie Mackintosh took the architecture world by storm when he combined a number of styles and came up with a distinctly art nouveau style.

Figure 12: Several chairs designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who clearly had a lot of very tall dinner guests.

Figure 13: One of Mackintosh’s stained glass windows.

Fortunately Mackintosh’s work is well persevered, and his distinct lettering and ornamentation is represented in a terrific typeface collection from International Typeface Corporation. With type designer Colin Brignall (Italia, Aachen Bold, etc.) as project director, and Tony Forster (Willow) as advisor, type master Phill Grimshaw drew a highly-detailed font that is a terrific tribute to the architect Mackintosh (see Figure 14).

Figure 14: ITC Rennie Mackintosh is a terrific font consisting of two type weights and an ornament collection.

McIntosh the Music Machine

When Apple decided to brand its new computer a Macintosh, they had to come to a trademark agreement with a small audio laboratory in Binghampton, New York. McIntosh tube amplifiers and other stereo gear had long been known as among the best in audio, as coveted for their looks as much as for their sound quality (see Figure 15). Finding a vintage McIntosh amp is as much of a fetish for some people as finding a vintage Mackintosh coat is for others.

Figure 15: A vintage McIntosh 240, as restored by Steve Hoffman. Devotion to this McIntosh brand is just as fanatic as for the other ones.

McIntosh Labs is still in business making high-end audio gear, and undoubtedly, like Apple Records, has had a few issues in recent times regarding Apple Computer’s foray into audio (see Figure 16). When both the McIntosh Labs and Apple Records trademark agreements were reached, no one imagined that someday Apple Computer would be a leading supplier of audio products.

Figure 16: It takes three days to complete a McIntosh stereo front panel, according to the maker. That’s considerably longer than it takes to make the front panel of an iPod.

Back to the Future, Again

So despite a number of other worthy Macintosh contenders, we have come to know the “Mac” as primarily the computer. But 20 years is a short time compared to the life of Mackintosh the clan, or McIntosh the apple, or Mackintosh the architect, or Mackintosh the coat, or even McIntosh the amplifier.

It could be that Macintosh, the computer, one day becomes a footnote in the history of Macintoshes, though like all the others, it will be known for its distinct style and sweet yet slightly tart taste.

Read more by Gene Gable.

A very well written historical review, with great examples.

Great work!

Thanks for the diverting column, Gene. You give me a giggle in the middle of a busy workday. And I love the vintage imgages!

Terri Stone

In a story that is so concerned with the various spellings of “Macintosh” and its ilk, a couple of spelling errors jumped out at me. The name of the Macintosh project’s creator is “Jef Raskin” (just one “f”). And, McIntosh Laboratory is based in “Binghamton” (no “p”), New York.

Is there more….?