Extending Tonal Range in Photoshop with Duotones

While they’re often used to colorize grayscale images, the original goal of multitones (duotones, tritones, and quadtones) was to expand the tonal range of the image. For instance, a 50 percent tint in gray ink may be lighter than an 11 percent spot of black ink; so an 11 percent spot of the gray ink is far lighter than the tonal range of black ink can achieve. If you print black ink in the shadows and gray ink in the highlights, you can achieve more levels of highlight grays.

On the other end of the spectrum, we usually think of 100 percent black ink as solid—you can’t get darker than that. But in reality, printing 100 percent black on top of 100 percent gray results in a darker, richer, denser black. Therefore, by adding the gray in the shadows, you expand the tonal range of the image even further toward real black.

Adding an ink is like listening to two of the blind men instead of just one; you get that much more information and can see the whole of the image that much more clearly.

Colorizing Images

When most designers think about duotones, they don’t think about expanding tonal range; they think about colorizing grayscale images. For instance, many newsletters are printed with two inks—black and some Pantone spot color. When given the opportunity to print with a second ink, many designers immediately think, “Oh, I can give some color to my grayscale images by making them duotones.”

There’s nothing wrong with colorizing a grayscale image. But colorizing images without thinking about the expanded tonal range usually looks pretty bad. In this section we talk about both, and how they relate to one another.

Duotones in Photoshop

There are two ways to create multitone images in Photoshop: Switch from Grayscale to Duotone under the Mode submenu, or create them in CMYK mode. We’re focusing our discussion on the Duotone mode and will cover CMYK mode later in this chapter.

In most color modes, each pixel’s color is described with multiple channels—CMYK color is made of four channels, RGB is made of three. Multitones are different. In a multitone image, Photoshop saves a single grayscale image along with two or more curves—one for each color plate. These curves are just like those in the Curves and Transfer Function dialogs (see Figure 1). Note that you can only create a duotone from an 8 bit/ channel grayscale image.

Figure 1: Duotone curves

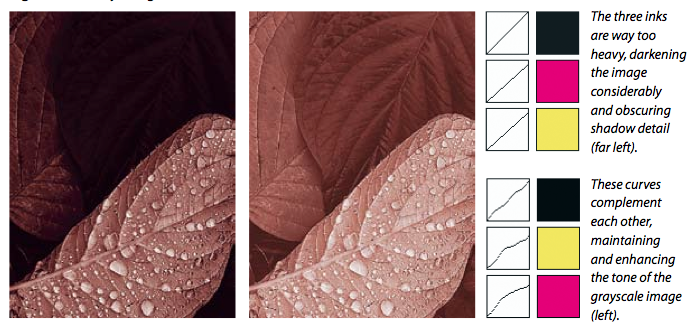

Because you’re typically replacing a single gray level with two or more tints of ink, you almost always need to adjust the amounts of ink used by each channel. Otherwise, the image appears too dark and muddy (see Figure 2). For instance, if you replace a 50 percent black pixel with 50 percent black and 50 percent purple, it appears much darker. Instead, replacing that 50 percent black with something like 30 percent black and 25 percent purple maintains the tone of that pixel. On the other hand, if the second color were much lighter, like yellow, you’d need much more ink to maintain the tone. You might, for example, use 35 percent black and 55 percent yellow.

Figure 2: Adjusting multitone curves

The duotone curves give you the ability to make these sorts of tonal adjustments quickly and with a minimum of image degradation because applying a duotone curve never affects the underlying grayscale image data. You can make 40 changes to the duotone colors or the curves and never lose the underlying image quality.

Note that we say the “underlying image quality” won’t suffer. We’re not saying that you can go hog-wild with the curves, and your final image will always look good. Far from it. In fact, duotones, tritones, and quadtones are often very sensitive and can quickly succumb to “lookus badus maximus.” But the image data saved on disk is unchanged by adjusting these curves; they’re like filters that are applied to the image data, but only when you view it on screen or print it out.

Use Curve Presets Unless you really know what you’re doing, just use the duotone curve sets that ship with Photoshop. We almost never create a multitone image from scratch. Instead, we click the Load button in the Duotone dialog, navigate to the Duotones folder (inside the Presets folder in the Adobe Photoshop application folder), and pick one from there. Then we make small tweaks to the curves, depending on the image.

- The first and second curves colorize the image (the first does so more than the second).

- The third curve of the set affects the midtones and three-quarter tones primarily, and does very little to the highlights. The effect is to warm or cool the image significantly without colorizing it much.

- The final duotone curve makes the image slightly warmer or cooler (still mostly neutral), primarily affecting the three-quarter tones.

Most of the curves come in sets of four:

If we’re using a Pantone color that’s not included in the canned presets, we usually pick a canned set for a color that has similar brightness to the one we’re using, and replace the color with ours. Then, depending on the two colors’ tones, we adjust the curves accordingly.

Checking each duotone channel The biggest hassle with images in Duotone mode is that you can’t see each channel by itself. If you make a tonal adjustment to an RGB or CMYK image, you can always go and see what that did to each channel. With a duotone, however, you’re in the dark. Here’s one way out: Convert the image to Multichannel mode.

While you’re in Multichannel mode, you can view each channel of the multitone image. The first channel corresponds to the first ink, the second to the second ink, and so on. When you’re done playing voyeur, select Undo (Command-Z in Mac OS X or Ctrl-Z in Windows), and you’re back where you started.

Dumb, fast duotones If we didn’t know how hectic life can get in a production setting, we would hardly believe how many people (printers, especially) still use the flat-tint duotone trick. The idea is that you can fake a duotone by laying a flat tint behind the grayscale image. For example, let’s say you want to add some blue to a grayscale image. To fake the duotone look, you could lay down an 11 percent tint of magenta or PMS 485 behind the entire image (see Figure 3), and set the image to overprint in your page-layout program.

Figure 3: Fake versus real duotones

Note that this really is an old printer’s trick, and it doesn’t look very good. Since you’re making no allowance for the tonal shift, fake duotones are often too dark and muddy. Photoshop makes creating real duotones so easy that faking it is hardly worth the effort. The quick-and-dirty method is quicker, but it’s not that much quicker, and it’s much dirtier.

Excerpted from Real World Adobe Photoshop by David Blatner, Conrad Chave

z and Bruce Fraser. Used with permission of Pearson Education, Inc. and Peachpit Press.

That made so much sense! Thank you!